Studies

BEFORE AND AFTER TREATMENT

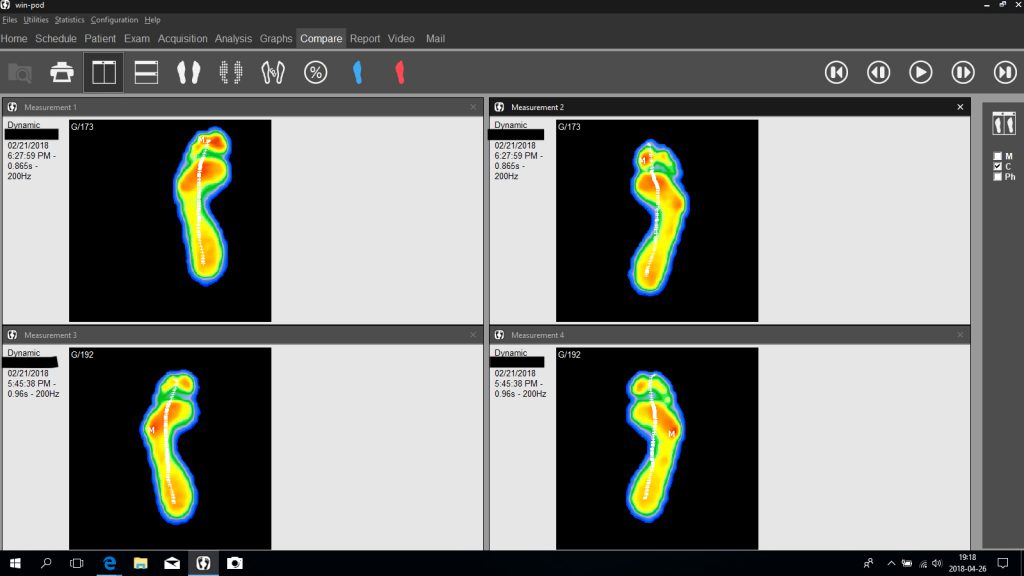

On the right is a Win-Pod analysis of the foot’s function before and after treatment—an elite-level athlete who feels weakness in his feet. In strength tests, the Tibialis Posterior is weak on both sides, and Functional Hallux Limitus appears in tests.

After the treatment, the strength and mobility of the toes restore. Before the treatment (lower analysis), the patient walks on the outside of the foot so as not to get over the big toe, with increasing pressure (red) (M) under the little toe. After the treatment, the patient can go over the big toe (red) and gain power with the correct chain of movement upwards, where the arch of the foot lifts with an outward rotation of the lower legs, which propagates upwards to the hip with a stretched knee, and which initiates the contraction of the seat.

It is crucial for someone who needs to perform in some way. The force must be able to transfer from the foot. If the foot’s arch does not come up, the foot collapses. Thus, the power does not develop where we want it.

SCANNING

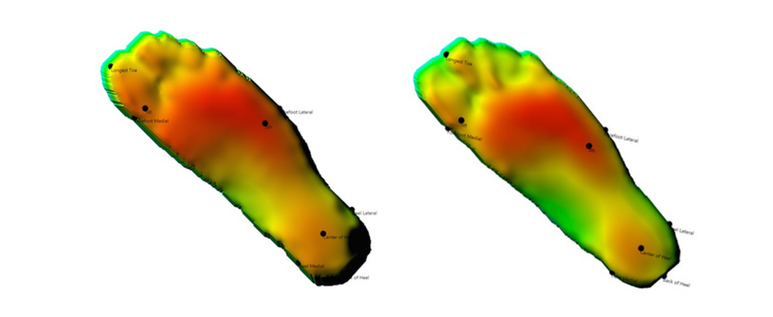

Here are two 3D scans of the sole of the foot. The left image shows the shape of the sole of the foot before stretching and the right image after 2 minutes of stretching.

You can see in the pictures that the longest toe before stretching is the big toe. After stretching, this changes to the second toe being longer. This is explained by the fact that the arch is raised and the big toe follows and looks shorter.

SQUAT

The pictures next to it show a person who has been treated for 2 x 6 minutes on both legs and ankles. As the pictures show, the person can squat deeper after the treatments.

FUNCTIONAL HALLUX LIMITUS BEFORE AND AFTER TREATMENT

Above are filmed Functional Hallux Limitus before and after treatment. You can see how the range of motion of the big toe has been restored. This improvement in movement occurs after all treatments without exception! Note that you should not force the big toe to get up in motion!

If you forcibly stress the joint, there is a risk that you damage the function of the foot where the big toe should lift the arch of the foot. The reason that the big toe does not bend is NOT in the big toe joint!

The upper film on the right shows the mobility of the big toe of a hallux valgus-operated woman. She had problems when running because her toe would become numb. We treated the stiffness in the big toe so that she could take the step over the big toe normally without the joint being compressed.

The treatment was done with the PRONATOS method with an effect on the ankle and the structures on the back of the lower leg, without treating the big toe itself.

With the treatment, we affect the stress in the joint of Hallux, which will lessen the stress in Hallux Valgus, Hallux Limitus and Hallux Rigidus. If this error persists, the load is forced on the outside of the foot, which will be overloaded. It leads to discomforts under the forefoot, such as Morton’s neuroma and other overload injuries.

It also stresses the outside of the ankle where the Fibula attaches. It is displaced upwards and stresses the upper Fibula joint on the outside of the knee. Because this joint capsule communicates with the knee joint capsule, this irritation can cause swelling in the knee joint. It is a difficultly diagnosed condition that is often missed with diffuse problems in the knee joint.

Limited mobility in the big toe also causes problems with the hip joint because you have to compensate for the stiffness in the big toe. Each step stresses rotation because you have to compensate for not walking normally over the big toe. Either you turn the foot in the sequence where you have the highest load in the hip joint, or you shorten the step with a harder push-off with the forefoot, which stresses the hip joint for each step.

RESEARCH

Research on Functional Hallux Limitus and Equinus / stiff calf muscles and conservative treatment.

Plantar Fasciitis and Its Relationship with Hallux Limitus

Conclusions

Hallux dorsiflexion was reduced in patients with PF who participated in the present study. This characteristic may have favored development of the pathologic abnormality by creating additional tension in the plantar fascia. The pronated foot was the most frequent type in the PF group. It is possible, therefore, that excessive subtalar pronation may be a biomechanical alteration that influences the etiology of PF.

Yolanda Aranda, PhD*, Pedro V. Munuera, DPM*

http://www.japmaonline.org/doi/abs/10.7547/0003-0538-104.3.263?code=pmas-site&journalCode=apms

Flexor Hallucis Longus Dysfunction

Lawrence M. Oloff, DPM, and S. David Schulhofer, DPM1

Conclusion

Anatomic pulley mechanisms exist to enhance tendonfunction, and the increased incidence of tendon injuryat these sites is well known. As a result of extrinsicand/or intrinsic repair processes, stenosing tenosynovitismay develop and normal range of motion may becomepainful and/or restricted. Flexor hallucis longus stenosingtenosynovitis is a well-recognized disorder among classical ballet dancers and is occasionally seen in running athletes. There are no reports concerning nonathletes and the disorder likely exists as a diagnosis of exclusion among the general population.

The prevalence of FHL stenosing tenosynovitis may be higher than reported. A relatively large number of patients were encountered during a short time frame; patients were primarily nonathletic, male, and two times the average reported age. In addition, overlapping signs and symptoms of FHL tendinitis, plantar fasciitis, and tarsal tunnel syndrome were present in many of the patients. Without a high index of suspicion, misdiagnosis may be encouraged, contributing to chronic FHL tendon injury that may decrease the opportunity for a nonoperative recovery.

The presence of plantar fasciitis that fails to respond to standard nonoperative protocols should be evaluated for FHL tendinitis. Many patients presented with an apparently painful medial plantar fascial band that was recalcitrant to nonoperative measures, yet obtained 100% pain relief during the tenogram anesthetic phase, and permanent relief after FHL tenolysis. Flexor hallucis longus stenosing tenosynovitis may be more prevalent than previously suspected and should be a diagnosis of inclusion among all patient populations with posterior ankle pain, medial arch pain, and/or tarsal tunnel symptoms. The term flexor hallucis longus dysfunction has been used to describe patients presenting with these unique features. Magnetic resonance imaging and tenography are valuable in establishing the diagnosis. FHL tenolysis has proven to be a relatively safe, successful, and reproducible procedure in recalcitrant cases.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9571456

Plantar pressure distribution in normal, hallux valgus and hallux limitus feet

- Bryant,* P. Tinley,† K. Singer†

CONCLUSIONS

Selected dynamic plantar pressure measurements of 30 control, 30 hallux valgus and 30 hallux limitus subjects, were analysed for significant differences. Hallux valgus feet demonstrated significant medial localization of peak and mean pressures, suggesting foot pronation is an important factor in the development of this condition. While hallux limitus feet showed a significant locus in mean pressure under the hallux, third and fourth metatarsal heads and lesser toes, indicating a degree of lateral bias forefoot load. From this work, it would appear that the functional pathomechanics of hallux valgus and hallux limitus feet are considerably different.

These findings may be of value in assessing and monitoring patients with forefoot pathology or screening individuals at risk of developing hallux valgus or limitus so that appropriate advice or interventative treatment may be considered.

A cross-reference of patients with posteromedial ankle pain, medial arch pain, and/or a positive Tinel’s sign

Functional Hallux Limitus and Lesser-Metatarsal Overload

James G. Clough, DPM*

Conclusion

The function of the first metatarsophalangeal joint may be most critical for normal foot function and for prevention of a host of foot pathologies. It has been shown that most normal feet demonstrate functional hallux limitus. A relatively simple treatment for this condition has been proposed, and it is hoped that this treatment will become another tool that clinicians will have at their disposal to treat functional hallux limitus and lesser-metatarsal overload and the resulting sequelae.

http://www.japmaonline.org/doi/abs/10.7547/0950593?journalCode=apms

Functional Hallux Limitus an unrecognized cause of Hallux Valgus or Hallux Rigidus. Review.

Authors:

* **Jacques Vallotton MD, FMH Orthopaedic Surgery, Sports Medicine. *Santiago Echeverri MD, MBA. FMH Orthopaedic Surgery.

*Vinciane Dobbelaere-Nicolas, Physiotherapist, Podologist.

Conclusion

The Functional Hallucis Limitus is a frequently misdiagnosed clinical entity and its effect on the evolution of Hallux Rigidus and Hallux Valgus has been underestimated. Its diagnosis is clinical and requires a high degree of suspicion. It is caused in the large majority of cases by a tenodesis effect on the Flexor Hallucis Longus tendon and can be demonstrated by the “Flexor Hallucis Longus Stretch Test” that is diagnostic. The tenodesis effect induces a sagittal plane blockade inducing a time lag during gait requiring a series of compensatory mechanisms that are not limited to the foot.

Functional Hallux Limitus deserves an early diagnosis and treatment to prevent the evolution of invalidating degenerative deformities on the MTP1: Hallux Rigidus and Hallux Valgus. Especially in the light of simple, effective diagnostic tests and low risk therapeutic options ranging from physiotherapy to endoscopic release of the Flexor Hallucis Longus tendon. Clinicians should look systematically for the presence of Functional Hallucis Limitus.

Functional Hallux Rigidus and the Achilles-Calcaneus-Plantar System

Ernesto Maceira, MD*, Manuel Monteagudo, MD

SUMMARY

Functional hallux rigidus is a clinical condition in which the mobility of the first MP joint is normal under non-weight-bearing conditions, but its dorsiflexion is blocked when the first metatarsal is made to support weight. It may be present in asymptomatic subjects or become incapacitating. Throughout its evolution, it goes from being a phenomenon that must be looked for to provide a diagnosis to a medical condition of florid arthrosis of the first MP joint. The author thinks that it is at the origin of mechanical hallux rigidus and is considered different phases of the same condition.

In mechanical terms, functional hallux rigidus implies a pattern of interfacial contact through rolling, while in a normal joint contact by gliding is established. The windlass mechanism is essential to maintain the plantar vault and is based on the correct functioning of an arch formed by several bony elements that work through compression and foot braces, which work through tension, among which the best prepared for its moment arm is the plantar aponeurosis. This forms a functional unit with the Achilles-calcaneal-plantar system, thanks to the enthesis/enthetic organ of the heel, meaning excessive traction of the triceps will be transmitted directly or indirectly to the fascia. Pronation of the foot and blockage of heel dorsiflexion may increase the tension in the aponeurosis. Both the elevation of the head of first metatarsal and the increase in tension in the aponeurosis may alter the joint dynamics in the first MP joint, producing contact by rolling instead of physiologic interfacial contact through gliding.

Furthermore, each one of these alterations may give rise to the other. Equinus due to the shortening of the elastic component of the calf muscles is a frequent finding among the general population, probably as a vestige of what our foot was millions of years ago. Limitation of the dorsiflexion in the ankle or the MP joint blocks the forward movement of the tibia during the stance phase on the sagittal plane, which is compensated through diverse mechanisms that entail abnormal movements on other planes and in other body segments. The compensatory mechanisms are usually tolerated well, but they may also produce pain or impairment, thus becoming medical conditions.

Orthopedic and surgical measures are at our disposition to treat the blockage of movement on the sagittal plane. Among the latter, the lowering and stabilizing of the head of first metatarsal and the lengthening of all or part of the triceps are favorable mechanical procedures to resolve the blockage.

Patients with functional hallux rigidus should only be operated on if the pain or disability makes it necessary. Gastrocnemius release is a beneficial procedure in most patients.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25456716

The Non-Surgical Treatment of Equinus.

Equinus deformity has been associated with over 96% of biomechanically-related foot and ankle pathologies.

http://www.podiatrym.com/pdf/2015/6/DeHeer615web.pdf

Hallux Rigidus Nonoperative Treatment and Orthotics

Remesh Kunnasegaran, MBChB (Glasgow), MRCS (Glasgow), Gowreeson Thevendran, MBChB (Bristol), MFSEM (UK), FRCS Ed (Tr & Orth)*

Plantar pressure distribution in normal, hallux valgus and hallux limitus feet

Bryant,* P. Tinley,† K. Singer†

SUMMARY

Although the literature is polarized by studies in support of operative management, there is a reasonable body of evidence to substantiate the role of nonoperative management for hallux rigidus. At present, there is conflicting evidence for the role of manipulation and injection therapy. There is weak evidence to support the role of orthotics and supportive shoes for the treatment of hallux rigidus and this treatment modality may be best suited for lower grades of hallux rigidus and selected groups of patients. There is a paucity of strong evidence to substantiate the role of physical therapy for hallux rigidus. The application of newer experimental modalities, such as extracorporeal shockwave therapy, iontophoresis, and ultrasonography therapy, although increasing in popularity, has yet to be shown to be an evidence-based practice for the treatment of hallux rigidus.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3819471/

The Effect of Sesamoid Mobilization, Flexor Hallucis Strengthening, and Gait Training on Reducing Pain and Restoring Function in Individuals With Hallux Limitus: A Clinical Trial

Jennifer Shamus, PT, PhD, CSCS1, Eric Shamus, PT, PhD, CSCS2, Rita Nacken Gugel, PhD3, Bernard S. Brucker, PhD, ABRP4, Cindy Skaruppa, PhD5

CONCLUSION

For health professionals working with individuals 26 to 43 years of age who have a painful but functional hallux limitus, a comprehensive program of physical therapy (including whirlpool, ultrasound, ice, electrical stimulation, and MPJ mobilizations and exercises) coupled with sesamoid mobilizations, flexor hallucis strengthening, and gait training appears to be more effective than a comprehensive physical therapy program alone. In our study, this treatment, when performed for 12 visits distributed over 4 weeks, resulted in a significant increase in hallucis ROM, strength, and function, and a significant decrease in pain. Given the results of the present study, physical therapists should consider this approach in the management of this condition.

http://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2004.34.7.368?code=jospt-site

The Effect of Gastrocnemius Tightness on the Pathogenesis of Juvenile Hallux Valgus: A Preliminary Study

Louis Samuel Barouk, MD. L. S. Barouk – Publications – ResearchGate

SUMMARY

Hallux valgus is the most frequent consequence of gastrocnemius tightness in the foot. This condition is particularly evident in juvenile hallux valgus. There are anatomic and biomechanical links between the gastrocnemius muscles and the hallux: Achilles tendon, calcaneum, plantar aponeurosis, plantar plate, and sesamoids. Thus gastrocnemius tightness exerts a deforming force on the hallux, which is well established for hallux limitus (windlass mechanism) but is not widely understood for hallux valgus. It is hoped that the present study addresses this. Isolated gastrocnemius tightness, through tension in the plantar aponeurosis and the oblique direction of its medial part, results in valgus and plantar deforming forces at the 1st MTPJ. This is defined as the oblique windlass mechanism, and causes, or at least is an exacerbating factor in the pathogenesis of, hallux valgus.

Clinical consequences for clinicians are, first, that it is essential to evaluate the gastrocnemius tightness in any case of juvenile hallux valgus, then to consider correcting this tightness each time it is required. This evaluation not only serves to secure the results of the bunionectomy but also to avoid, diminish, or at least to ensure the success of surgery of the lesser rays in cases of metatarsalgia. In addition, it corrects other signs of gastrocnemius tightness: lumbago, cramps or calf tension, difficulty walking in bare feet or flat shoes, and eventually hindfoot problems (ie, Achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis).

https://www.researchgate.net/profile/L_Barouk/publications

The Effect of the Gastrocnemius on the Plantar Fascia

Javier Pascual Huerta, PhD

SUMMARY

In this article, a functional relationship has been proposed between both structures that goes beyond a simple anatomic relationship. From the model presented herein, tightness of the gastrocnemius muscle produces an increase in Achilles tendon tension during weight-bearing activities and increasing dorsiflexion stiffness of the ankle joint. Increased tension in the Achilles tendon during weight-bearing produces plantarflexion moments at the hind foot and an increase in forefoot plantar pressure with an anterior displacement of center of pressure. The combination of hind foot plantarflexion moments and forefoot dorsiflexion moments tend to collapse the arch, and the plantar fascia increases its passive mechanical longitudinal tension counteracting the arch flattening effect of gastrocnemius tightness. With these ideas in mind, the relationship between the gastrocnemius muscle and the plantar fascia could be considered as a relationship derived from the mechanical behavior of the foot in weight-bearing conditions instead of direct transmission of tension through the calcaneal trabecular system. Although the model presented has some limitations, such as the effect of intrinsic foot and deep posterior calf muscle contraction, it can serve for a better understanding of the effect of gastrocnemius tightness in specific foot disorders.

These ideas can also help to explain clinical findings of patients with gastrocnemius tightness and open new possibilities of treatment for specific foot problems, such as plantar fasciitis, metatarsalgia, midfoot dorsal pain, and forefoot ulcerations of neuropathic patients.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25456717

Gastrocnemius Shortening and Heel Pain

Matthew C. Solan, FRCS (Tr&Orth)a,b,c,d,*, Andrew Carne, FRCRa, Mark S. Davies, FRCS (Tr&Orth)d

SUMMARY

Contracture of the gastrocnemius produces subtle alterations to gait and posture.

There is a resultant increase in the strain in the Achilles tendon and also the plantar fascia. Patients with recalcitrant heel pain commonly have isolated gastrocnemius contracture that can be shown using the Silfverskiold test.

Eccentric calf stretching is one of the few interventions that has been proved to be useful in the management of plantar fasciopathy and Achilles tendinopathy. As part of the investigation and management of recalcitrant heel pain any contracture of the gastrocnemius should be identified using the Silfverskio¨ ld’s method. If formal eccentric stretching of the gastrocnemius does not result in improvement in the symptoms and the contracture persists, then surgical gastrocnemius lengthening should be considered. PMGR is the preferred technique for most patients because the recovery is rapid, the procedure has a very low morbidity, and it can be performed under local anesthesia with sedation (avoiding the need for full GA in the prone position). If there is extreme contracture then the surgeon must decide whether to release the lateral head of the gastrocnemius proximally at the same time or perform a Strayer procedure instead.

Local treatments for either the Achilles tendon or the plantar fascia should be deferred until any calf contracture has been corrected, which is often by stretching under physiotherapy supervision, but orthopedic surgeons should be aware of the occasional need for gastrocnemius lengthening. The PMGR technique, developed by L.S. Barouk and P. Barouk in France, is an excellent method with extremely good functional results, a low risk of complications, no need for postoperative immobilization, and once mastered is performed under local anesthetic. In time this will become the technique of choice for gastrocnemius lengthening. In our practice the Strayer is reserved for extreme contracture only and in 95% of cases we prefer the Barouk method.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25456718

Functional Hallux Limitus A Review

Beverley Durrant, MSc, BSc(Hons) Pod*, Nachiappan Chockalingam, PhD†

Conclusions

In reviewing the literature on functional hallux limitus and the reported effects that it may have on gait, it becomes clear that the plethora of available information provides the reader with a vast array of both scientific evidence and theoretical debate. Many of the clinical tests carried out in practice are based on historical approaches and anecdotal findings. New research and theories based on these methods may run the risk of adding to the already confusing minefield of opinion and theoretical reasoning rather than providing clinicians with sound scientific research on which to base their practice. Nevertheless, the way in which some new theories are being challenged is encouraging and is demonstrative of how evidencebased practice is being embraced. Perhaps the way forward is to continue the debate and encourage clinicians to engage in quantitative research that uses robust, valid, repeatable, and reliable clinical measures that will provide empirical primary research to underpin the theory and provide evidencebased practice for the future. This is particularly important in foot function because it is the only part of the body in contact with the ground during bipedal ambulation. Further research must include the effect that abnormal foot function may have on more proximal structures, and therefore collaborative multidisciplinary research would be useful. The use of motion analysis gives a way forward for researchers to gather accurate kinematic data, and perhaps using this method for data collection may go some way to provide a standardized framework for kinematic analysis of the small joints of the foot that are often difficult to measure.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24433088_Functional_Hallux_Limitus

Dorsal flexion in the first metatarsophalangeal joint and navicular position in exercisers with Achilles tendinopathy in the middle portion

Gunilla Vogel

Conclusion: Exercisers with unilateral AT have decreased dorsiflexion in the MTP 1 joint on the affected side compared to healthy. There do not appear to be any side differences regarding the navicular position. GM is preferable to VE in clinical measurement of dorsiflexion in the MTP 1 joint, as mobility was underestimated in VE

http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:812031/FULLTEXT04.pdf

Patel A, DiGiovanni B. Association between plantar fasciitis and isolated contracture of the gastrocnemius. Foot Ankle Int (2011) 32:5–8. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0005

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Tong KB, Furia J. Economic burden of plantar fasciitis treatment in the United States. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) (2010) 39:227–31. doi:10.1185/030079907X199790

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Abbassian A, Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Solan MC. Proximal medial gastrocnemius release in the treatment of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int (2012) 33:14–9. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0014

Abdulmassih S, Phisitkul P, Femino JE, Amendola A. Triceps surae contracture: implications for foot and ankle surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg (2013) 21:398–407. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-398

Amis J. The gastrocnemius: a new paradigm for the human foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:637–47. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Anderson JG, Bohay DR, Eller EB, Witt BL. Gastrocnemius recession. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:767–86. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.09.001

Armstrong DG, Stacpoole-Shea S, Nguyen H, Harkless LB. Lengthening of the Achilles tendon in diabetic patients who are at high risk for ulceration of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am (1999) 81:535–8.

Aronow MS, Diaz-Doran V, Sullivan RJ, Adams DJ. The effect of triceps surae contracture force on plantar foot pressure distribution. Foot Ankle Int (2006) 27:43–52.

Aronow M. Triceps surae contractures associated with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Tech Orthop (2000) 15:164–73. doi:10.1097/00013611-200015030-00002

Barouk LS. The effect of gastrocnemius tightness on the pathogenesis of juvenile hallux valgus: a preliminary study. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:807–22. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.005

Barske HL, DiGiovanni BF, Douglass M, Nawoczenski DA. Current concepts review: isolated gastrocnemius contracture and gastrocnemius recession. Foot Ankle Int (2012) 33:915–21. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0915

Bolívar YA, Munuera PV, Padillo JP. Relationship between tightness of the posterior muscles of the lower limb and plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int (2013) 34:42–8. doi:10.1177/1071100712459173

Bowers AL, Castro MD. The mechanics behind the image: foot and ankle pathology associated with gastrocnemius contracture. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol (2007) 11:83–90. doi:10.1055/s-2007-984418

Cazeau C, Stiglitz Y. Effects of gastrocnemius tightness on forefoot during gait. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:649–57. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.003

Chen WM, Park J, Park SB, Shim VPW, Lee T. Role of gastrocnemius-soleus muscle in forefoot force transmission at heel rise – a 3D finite element analysis. J Biomech (2012) 45:1783–9. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.04.024

Crawford F, Thomson C. Interventions for treating plantar heel pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2003) 3:CD000416.

Cychosz CC, Phisitkul P, Belatti DA, Glazebrook MA, DiGiovanni CW. Gastrocnemius recession for foot and ankle conditions in adults: Evidence-based recommendations. Foot Ankle Surg (2015) 21:77–85. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2015.06.001

DiGiovanni CW, Kuo R, Tejwani N, Price R, Hansen ST Jr, Cziernecki J, et al. Isolated gastrocnemius tightness. J Bone Joint Surg (2002) 84:962–70.

DiGiovanni CW, Langer P. The role of isolated gastrocnemius and combined Achilles contractures in the flatfoot. Foot Ankle Clin (2007) 12:363–79. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2007.03.005

Frykberg RG, Bowen J, Hall J, Tallis A, Tierney E, Freeman D. Prevalence of equinus in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc (2012) 102:84–8. doi:10.7547/1020084

Gentchos CE, Bohay DR, Anderson JG. Gastrocnemius recession as treatment for refractory achilles tendinopathy: a case report. Foot Ankle Int (2008) 29:620–3. doi:10.3113/FAI.2008.0620

Harris RI, Beath T. Hypermobile flat-foot with short tendo achillis. J Bone Joint Surg (1948) 30:116–50.

Hill RS. Ankle equinus. prevalence and linkage to common foot pathology. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc (1995) 85:295–300. doi:10.7547/87507315-85-6-295

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hoke M. An operation for the correction of extremely relaxed flat feet. J Bone Joint Surg (1931) 13:773–83.

Johnson E, Bradley B, Witkowski K, McKee R, Telesmanic C, Chavez A, et al. Effect of a static calf muscle-tendon unit stretching program on ankle dorsiflexion range of motion of older women. J Geriatr Phys Ther (2007) 30:49–52. doi:10.1519/00139143-200708000-00003

Kibler WB, Goldberg C, Chandler TJ. Functional biomechanical deficits in running athletes with plantar fasciitis. Am J Sports Med (1991) 19:66–71. doi:10.1177/036354659101900111

Kiewiet NJ, Holthusen SM, Bohay DR, Anderson JG. Gastrocnemius recession for chronic noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int (2013) 34:481–5. doi:10.1177/1071100713477620

Laborde JM. Bilateral proximal fifth metatarsal nonunion treated with gastrocnemius-soleus recession. JBJS Case Connect (2013) 3:e68. doi:10.2106/JBJS.CC.M.00021

Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Diabetex Research Group. Ankle equinus deformity and its relationship to high plantar pressure in a large population with diabetes mellitus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc (2002) 92:479–82. doi:10.7547/87507315-92-9-479

Lin SS, Lee TH, Wapner KL. Plantar forefoot ulceration with equinus deformity of the ankle in diabetic patients: the effect of tendo-Achilles lengthening and total contact casting. Orthopedics (1996) 19:465–75.

Maceira E, Monteagudo M. Functional hallux rigidus and the Achilles-calcaneus-plantar system. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:669–99. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.006

Macklin K, Healy A, Chockalingam N. The effect of calf muscle stretching exercises on ankle joint dorsiflexion and dynamic foot pressures, force and related temporal parameters. Foot (Edinb) (2012) 22:10–7. doi:10.1016/j.foot.2011.09.001

Martin RL, Irrgang JJ, Conti SF. Outcome study of subjects with insertional plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int (1998) 19:803–11. doi:10.1177/107110079801901203

Maskill JD, Bohay DR, Anderson JG. Gastrocnemius recession to treat isolated foot pain. Foot Ankle Int (2010) 31:19–23. doi:10.3113/FAI.2010.0019

McGlamry ED, Kitting RW. Aquinus foot. An analysis of the etiology, pathology and treatment techniques. J Am Podiatry Assoc (1973) 63:165–84. doi:10.7547/87507315-63-5-165

Monteagudo M, Maceira E, Garcia-Virto V, Canosa R. Chronic plantar fasciitis: plantar fasciotomy versus gastrocnemius recession. Int Orthop (2013) 37:1845–50. doi:10.1007/s00264-013-2022-2

Norregaard J, Larsen CC, Bieler T, Langberg H. Eccentric exercise in treatment of Achilles tendinopathy. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2007) 17:133–8.

Park DY, Rubenson J, Carr A, Mattson J, Besier T, Chou LB. Influence of stretching and warm-up on Achilles tendon material properties. Foot Ankle Int (2011) 32:407–13. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.0407

Pascual-Huerta J. The effect of the gastrocnemius on the plantar fascia. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:701–18. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.011

Pratt K, Bohannon R. Effects of a 3-minute standing stretch on ankle-dorsiflexion range of motion. J Sport Rehabil (2003) 12:162–73.

Radford JA, Burns J, Buchbinder R, Landorf KB, Cook C. Does stretching increase ankle dorsiflexion range of motion? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med (2006) 40:870–5. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.029348

Rao SR, Saltzman CL, Wilken J, Yak J. Increased passive ankle stiffness and reduced dorsiflexion range of motion in individuals with diabetes mellitus. Foot Ankle Int (2006) 27:617–22.

Reimers J, Pedersen B, Brodersen A. Foot deformity and the length of the triceps surae in Danish children between 3 and 17 years old. J Pediatr Orthop B (1995) 4:71–3. doi:10.1097/01202412-199504010-00011

Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg (2003) 85:872–7.

Roos EM, Engstrom M, Lagerquist A, Soderberg B. Clinical improvement after 6 weeks of eccentric exercise in patients with mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy – a randomized trial with 1-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports (2004) 14:286–95. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.378.x

Sgarlato TE, Morgan J, Shane HS, Frenkenberg A. Tendo achillis lengthening and its effect on foot disorders. J Am Podiatry Assoc (1975) 65:849–71. doi:10.7547/87507315-65-9-849

Solan MC, Carne A, Davies MS. Gastrocnemius shortening and heel pain. Foot Ankle Clin (2014) 19:719–38. doi:10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.010

Subotnick SI. Equinus deformity as it affects the forefoot. J Am Podiatry Assoc (1971) 61:423–7. doi:10.7547/87507315-61-11-423

Szames SE, Forman WM, Oster J, Eleff JC, Woodward P. Sever’s disease and its relationship to equinus: a statistical analysis. Clin Podiatr Med Surg (1990) 7:377–84.

Tabrizi P, McIntyre WM, Quesnel MB, Howard AW. Limited dorsiflexion predisposes to injuries of the ankle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br (2000) 82:1103–6. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.82B8.10134

Verrall G, Schofield S, Brustad T. Chronic Achilles tendinopathy treated with eccentric stretching program. Foot Ankle Int (2011) 32:843–9. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.0843

Wapner KL, Sharkey PF. The use of night splints for treatment of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int (1991) 12:135–7. doi:10.1177/107110079101200301

Zimny S, Schatz H, Pfohl M. The role of limited joint mobility in diabetic patients with an at-risk foot. Diabetes Care (2004) 27:942–6. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.4.942

Duthon VB, Lubbeke A, Duc SR, Stern R, Assal M. Noninsertional Achilles tendinopathy treated with gastrocnemius lengthening. Foot Ankle Int (2011) 32:375–9. doi:10.3113/FAI.2011.0375

Klein SE, Dale AM, Hayes MH, Johnson JE, McCormick JJ, Racette BA. Clinical presentation and self-reported patterns of pain and function in patients with plantar heel pain. Foot Ankle Int (2012) 33:693–8. doi:10.3113/FAI.2012.0693

Porter D, Barrill E, Oneacre K, May BD. The effects of duration and frequency of achilles tendon stretching on dorsiflexion and outcome in painful heel syndrome: a randomized, blinded, control study. Foot Ankle Int (2002) 7:619–24. doi:10.1177/107110070202300706

Nutt J. Diseases and Deformities of the Foot (E. B. Treat & Co.). Google Digital Copy (1913). Available from: http://books.google.com/books?id=UWgQAAAAYAAJ

Silfverskiöld N. Reduction of the uncrossed two-joints muscles of the leg to one-joint muscles in spastic conditions. Acta Chir Scand (1924) 56:315–30.

Gajdosik R, Vander Linden D, McNair P, Williams A, Riggin T. Effects of an eight-week stretching program on the passive-elastic properties and function of the calf muscles of older women. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) (2005) 20:973–83. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.05.011

Perry J. Gait Analysis: Normal and Abnormal Function. Thorofare, NJ: SLACK International (1992).

Phisitkul P, Rungprai C, Femino JE, Arunakul M, Amendola A. Endoscopic gastrocnemius recession for the treatment of isolated gastrocnemius contracture: a prospective study on 320 consecutive patients. Foot Ankle Int (2014) 35:747–56. doi:10.1177/1071100714534215

Gill LH, Kiebzak GM. Outcome of nonsurgical treatment for plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int (1996) 17:527–32. doi:10.1177/107110079601700903

Gurdezi S, Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Solan MC. Results of proximal medial gastrocnemius release for Achilles tendinopathy. Foot Ankle Int (2013) 34:1364–9. doi:10.1177/1071100713488763

Riddle DL, Schappert SM. Volume of ambulatory care visits and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with plantar fasciitis: a national study of medical doctors. Foot Ankle Int (2004) 25:303–10.

Trent V. An Investigation into the Effect of Stretching Frequency on Range of Motion at the Ankle Joint. Masters Thesis. Auckland: Auckland University of Technology (2002).

Faber F, Anderson M, Sevel C, Thorbozrg K, Bandholm T, Rathleff M. The majority are not performing home-exercises correctly two weeks after their initial instruction–an assessor-blinded study. PeerJ (2015) 3:e1102. doi:10.7717/peerj.1102

Sciberras N, Gregori A, Holt G. The ethical and practical challenges of patient noncompliance in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am (2013) 95:e61. doi:10.2106/JBJS.L.00483

Atkins D, Crawford F, Edwards J, Lambert M. A systematic review of treatments for the painful heel. Rheumatology (Oxford) (1999) 38:968–73. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/38.10.968

Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Rodriguez Sanz D, Prados Frutos JC, Salvadores Fuentes P, Chicharro JL. Plantar pressures in children with and without Sever’s disease. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc (2011) 101:17–24. doi:10.7547/1010017